Work live, unplugged

The argument that is most often made to justify forcing remote workers to return to the office is the increased creativity, camaraderie, and opportunity for ad-hoc collaboration. To be clear, I am very much in favour of all of these things! But they are not sufficient alone. What you need is balance between creative collaboration and focused alone time.

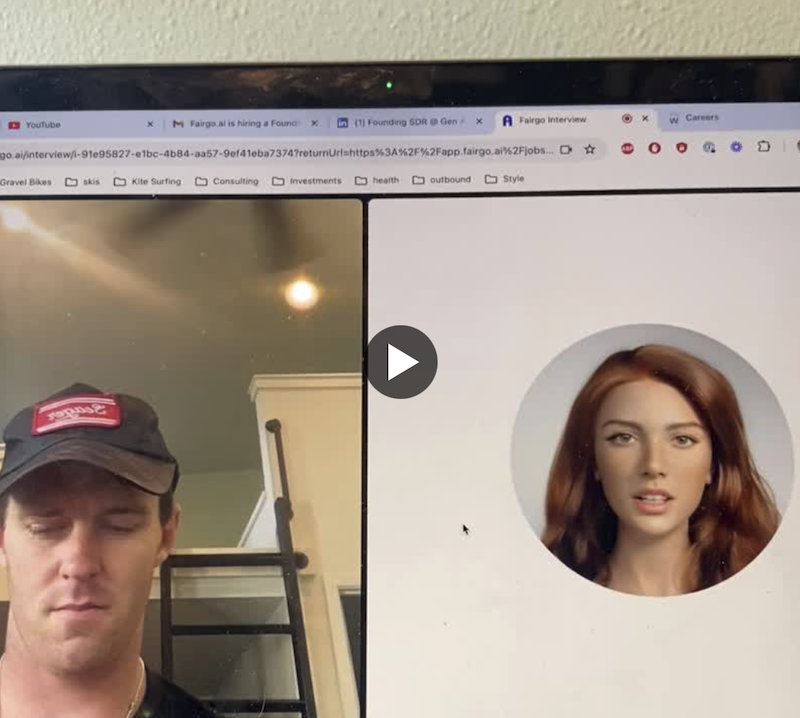

I do wonder how that balance is going to shift as we add AI tools that purport to give many of the benefits of (human) collaboration. Already we are seeing AI avatars interviewing human candidates. It is not at all clear to me that this is any better than simple keyword-matching on CVs (and of course consumes far more time and resources), but it definitely seems like the sort of idea that could only arise from a remote-work situation.

Much as we saw with the return to in-person events as soon as the first wave of Covid lockdowns had passed, I expect that there will be a renewed increase in the premium placed on in-person professional interactions, not just for their own benefits, but simply to be certain that you are talking to a real person and not some GenAI simulacrum.

We already see a similar mix of revealed preferences and economic factors at play when it comes to live music, with demand driving astronomical pricing because of the built-in scarcity (Oasis and Taylor Swift only play so many gigs). The in-person experience beats the convenience of streaming music, which these days may well be itself generated or at least assisted by GenAI.

Back to the office, the introduction of AI-enabled features in so much of the software we use at work is already changing the nature of our relationships with colleagues and managers. This is possible because

Much organisational language is static rather than dynamic, intended not to spur original thought but to align everyone on a shared understanding of internal rules and norms. […] Organisational ceremonies, such as the annual performance evaluations that can lead to employees being promoted or fired, can be carried out far more quickly and easily with llms. All the manager has to do is fire up ChatGPT, enter in a brief prompt with some cut-and-pasted data, and voilà! Tweak it a little, and an hour’s work is done in seconds. The efficiency gains could be remarkable.

And perhaps, sometimes, efficiency is all we care about. If a ritual is performed just to affirm an organisational shibboleth, then a machine’s words may suit just as well, or even better.

That static language is of course perfectly to the capabilities of today’s Large Language Models — but the question that needs to be asked, as about so many of the uses of LLMs, is why are we doing this? My attitude remains “if you couldn’t be bothered to write it, I can’t be bothered to read it” — and if you are using AI to generate a long email from three bullet points, and I am (lossily) recondensing it back down to three bullet points, what exactly has been achieved?

This same objection applies to much of the return-to-office hysteria. If I am travelling to an office, but my team is all sitting in different offices, and we are all on video calls with each other, what exactly has been achieved? No spontaneous hallway collaboration is happening; people in that situation can literally die at their desks and not be found for days.

The pushback against remote work started very early on after Covid lockdowns ended, but it is becoming clear what a return-to-office mandate actually means:

The minority of corporations that have managed to enforce full-time office attendance fall into two main categories. First, there are those, like Goldman Sachs, that are profitable enough to pay salaries that more than offset the cost and inconvenience of commuting to work, whether or not they gain extra productivity as a result. Second, there are companies like Grindr and Twitter (now X) that are looking for massive staff reductions and don’t care much whether the staff they lose are good or bad.

With 83% of CEOs expecting a full return to the office within three years, according to a KPMG study cited by that same Guardian article, the obvious question is what we expect the breakdown between those two categories to be.

Once again, there needs to be sensible balance. Some days, my main contribution at work is a couple of thousand words that are deeply thought out and represent the crystallisation of my couple of decades of experience. Working from home gives me the quiet time to produce those, in a way that open-space office environments simply don’t. Vice versa, sometimes the most effective way to figure something out is to get a handful of people around a whiteboard and draw it out — and no, pushing cursors across the screen in Figma or whatever doesn’t work in the same way. And a lot of the time you are in between those two states, so a quick Zoom check-in or whatever makes sure that everyone is aligned and delivering on what was planned at that whiteboard.

There needs to be an office, but it should not be a place where we go just to cosplay someone’s idea of “work” — and AI should not be used to accelerate the performance of performative busyness. Commuting to an office is expensive, obviously for employees who pay directly with their own money and time, but also for employers who get stressed-out employees who take more half-days or even full days for chores that would have been easy to slot into a remote-work schedule. Expensive things can still be worth their cost; we just need to make sure we are not squandering that expense, and making our time at work count.

🖼️ Screenshot of AI avatar interview from Jack Ryan, photo by Andrea De Santis on Unsplash