Translation, lost in translation

The definition of translation is getting lost in translation.

I had this piece from the Guardian stuck in my drafts for a while, and finally got around to writing about it. The question of whether, first automation, and now AI, can replace human translators is a common one, dating back at least to the launch of Google Translate.

The article gets into it right from the (Betteridge-compliant) question in its sub-head: “can AI replace translators?” There is a lot of nuance around what that means exactly, but in this case it quickly becomes clear that we are talking about a publisher, Veen Bosch & Keuning, which intends to use AI translation for commercial fiction. This announcement has, according to the article, “outraged both authors and translators”, but I am pretty outraged as a reader as well. I try not to read in translation, at least for languages that I speak well enough to read in, precisely because so many translations are just not that good. I cannot imagine generative AI doing a better job than proper human translators.

Any translation is a tight-rope between factual accuracy — that is, being faithful to the source — and literary expression in the target language. Even something like a user manual for a technical product cannot blindly jettison felicity of phrasing in search of ultimate precision, otherwise a reader will struggle to understand what is being communicated. But translating literary fiction is itself a literary endeavour. The translator is effectively both writing a new book in the target language, and making it reflect the original book in the source language. This is the essence of human expression, and cannot be condensed by automation, no matter how advanced.

In the moment or for the record

There is a confusion here between translation in the moment and translation for the record. In the first case, I just need the raw technical content: what does this street sign mean, what are the ingredients of this dish on the menu, what is this scary warning about. In this case, machine translation is fine; I don’t travel with my personal interpreter, so if I am in a place where I don’t speak the language, being able to point my phone at something and get the gist of what is going on is really useful. That’s not to say there is no value in learning languages, mind. But there is only so much time, and unless you only travel within a specific limited set of countries, you will eventually end up in a place where people speak a language that you don’t. Then these automated-translation tools become really useful.

Translation for the record is a whole different kettle of fish.1 Even translating something like a corporate website will require careful review by expert humans. The idea of putting out automated translations of literary fiction is simply abhorrent. It simply can’t work well, except for the most generic regurgitated homogenised narrative product.

The implication is that once again there is something else going on.

found out that one of my best clients that quiet-fired me and replaced me with machine translation is now trying to hire a reviser to do twice the work at a 10th of the rate. that’s how it works, folks: they fire you and replace you with a miracle AI app, then they try to rehire you at a huge pay cut to clean up the mess.

Of course this sort of trade-off between artisanal human-powered quality and automated production at scale has always happened, and as described above, there are beneficial aspects too. If (lower-quality) automated translation is universally available in the moment, that is a net benefit to humanity. Vanishingly few people can afford full-time personal interpreters, but (to a first approximation) everybody has a smartphone and can access these tools. The problems arise when the lower-quality automated approach is being applied inappropriately in a situation that does call for the artisanal hand-crafted approach.

The difference in perception is due to the fulcrum where the economies of scale get applied. Once a book is translated, the contents of each copy of the translated work are identical. Reducing the cost of creating that initial translation will have negligible effect on the marginal cost — that is, the cost of producing each individual book. Thus, no measurable benefit to humanity.

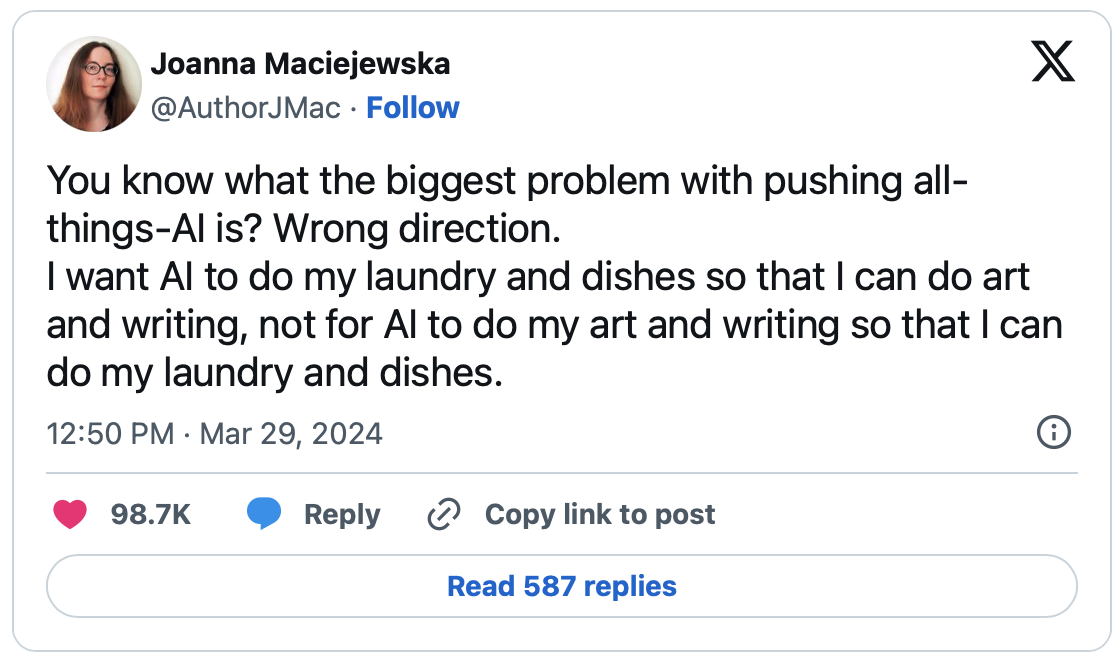

From Joanna Maciejewska on Twitter

From Joanna Maciejewska on Twitter

What bothers people especially about some of the more breathless hype around the current wave of AI is precisely that mismatch: the feeling that the tools are being used, not to help people, but to add one more tiny sliver of profit to a company’s balance sheet, regardless of the damage that is done to people. When I read a book, I want that human touch, the magic of one mind reaching out to another and causing images and feelings to appear, via nothing more advanced than plain text on a page.

The sort of mind that could conceive of inserting automated translation into that communion probably only reads horrible business-book pablum, or worse, has AI-generated summaries read to them at 2x speed. Go listen to the If Books Could Kill episode on Who Moved My Cheese? instead; it will be a better use of your time.

🖼️ Photos by Edurne Tx on Unsplash

-

That is actually a perfect example: try translating that particular bit of idiom! Sure, these days at least some machine-translation systems are smart enough not to translate a phrase like that literally, but the way you translate it is still very context-dependent. ↩