Soft Synthesis Machine

Because of ChatGPT, many people consider that AI must necessarily look like a chatbot. The reality is that the chat interface was a great technology demonstrator, but will probably end up being something of a blind alley in terms of developing AI applications that people actually use. Now is the right time to think about what those future AI-enabled services could look like and how they should be built.

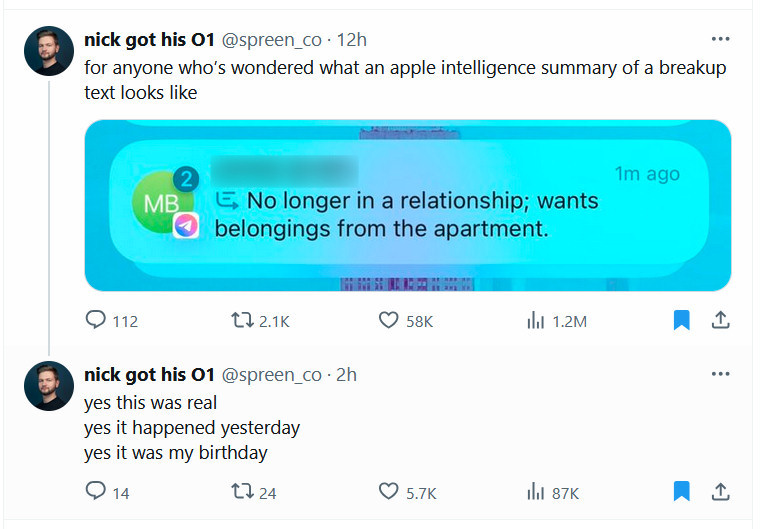

One of the ways in which people might already use AI without interacting with a chatbot is through the summarisation capabilities that Google is adding to search or Apple is adding to iOS. The promise is that the AI will synthesise information, whether from an email thread or from across the web or whatever data sources apply, and give a concise view to the user. However, as Mike Caulfield puts it:

“when I don’t synthesize myself, I miss important things I learn while synthesizing”. There is a value in reading widely that is lost when we just let the machine do it.

The reason is that we humans tend to accept at least the framing that is put in front of us fairly uncritically. This is bad enough in the case of an incomplete summary of an email thread, although a miss there is fairly easy to verify and correct.

The problem is, as Ben Thompson (paywall) flags, with the Rumsfeldian “unknown unknowns”. If I know to ask a question, and have an idea of the shape of the answer, AI can help me fill in the blanks. It’s a lot less helpful if I don’t even know to ask the question — if I don’t know what I don’t know. And because it answers so confidently, users tend to accept the output fairly uncritically.

This fits with studies that show AI as having reduced benefits for power users, who are performing that synthesis for themselves — and deriving the benefits of doing so.

The same mechanism is at play with the generative side of AI, with a new study from Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University worrying that these “technologies can and do result in the deterioration of cognitive faculties that ought to be preserved”.

The problem is that people are not great at taking over from automated systems, whether at identifying that the system is straying from the intended outcome, or at correcting the error in a timely manner.

Apple was forced to halt Apple Intelligence summaries of news articles after factual errors were included in those summaries. This was embarrassing for Apple, but is it a problem in the real world? Potentially: what if an automated summary caused people to take action, such as evacuating (or not) in the face of a wildfire or other disaster? Or what if a summary moved the stock market, much as we used to worry about a tweet doing?

Who Watches The Operator?

When an accident occurs and is blamed on “operator error”, that is a sign of a system design failure. A system that is so fragile that an operator’s error can cause a disaster is a system that is poorly designed. The most famous example of such a design failure is the Therac-25, an X-ray machine that had a failure mode which resulted in patients receiving 100 times the intended does of radiation. Three people died as a result of failures in both the hardware and the software design of the system.

Fortunately, not all failures have quite such tragic consequences. However, the reason the story of the Therac-25 is still known and taught in universities is as a cautionary tale. While individual failures can occur, it takes multiple failures occurring in concert to cause an accident. In the case of the Therac-25, these included lack of software testing, the removal of hardware interlocks that were present in previous generations of the machine, and incomplete operator documentation.

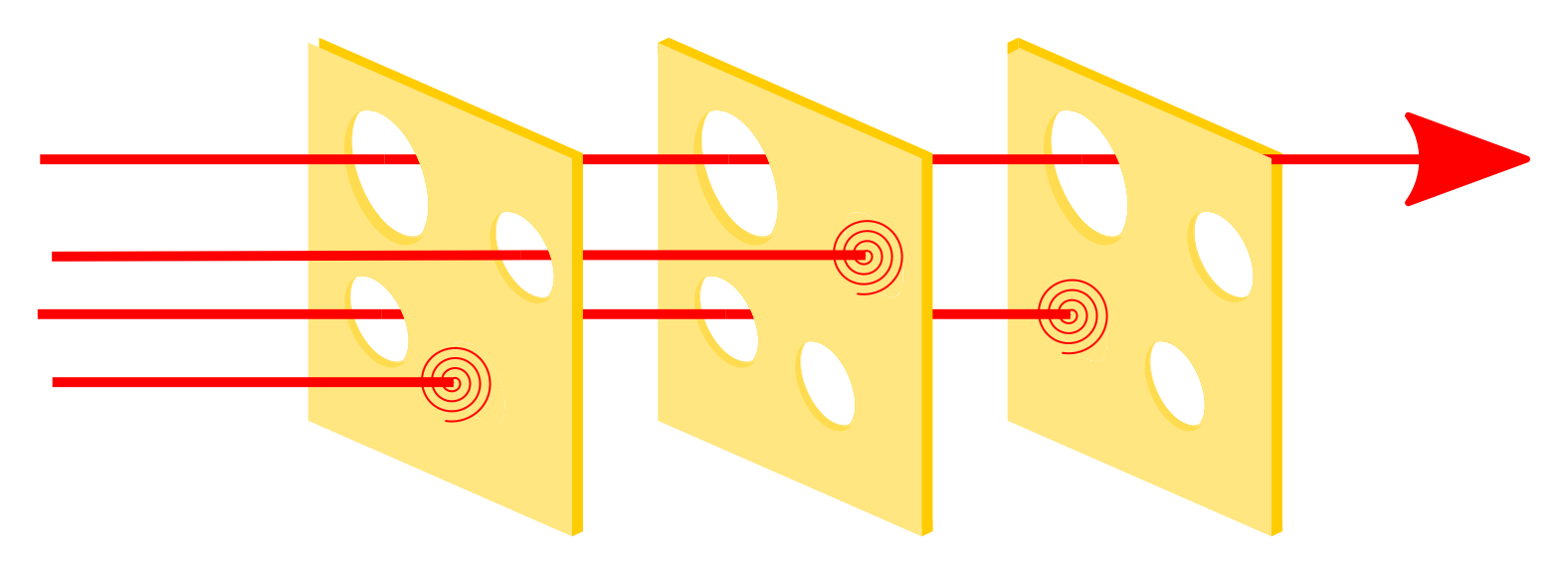

The way we address these issues is not by trying to design a single impenetrable monolith of a system, but with a layered approach, known as the “Swiss cheese model”. No one layer of defence against accident can be perfect, but with enough layers, it becomes more and more improbable that the holes in each layer would align perfectly, allowing an accident to take place.

It’s still early days for GenAI, but software engineering and system design are mature practices.1 Good design practice needs to consider failure modes, especially ones like LLM hallucinations that are likely and well-known at this point. Sanity checks on model outputs should be considered as best-practices at this point.

The need for these checks is why the LLMs themselves are not products; they are components of larger products, and those products need to be designed carefully. A search engine that offers a generated summary of results is dependents on the content of those search results. The search results may be incorrect or incomplete, and the LLM may in turn hallucinate while correlating and summarising them. Those are not failures of those components which can be improved over time; they are intrinsic in how they operate. A search engine can only present what it finds on the web, and LLMs work by converging on statistically probable output. However, presenting the resulting summary uncritically as fact is a failure — not of AI, but of good service design.

You can get away with hiding behind a “beta” flag for a little while, but once you start turning on the feature by default for all users, that becomes more than a little hypocritical. Instead, take the time to design the complete service with care, including specifically the interaction between the various components — both AI and non-AI. Robust service design allows for each layer to be unreliable and compensates for that fallibility in both design and operation. GenAI is no different, and the excuse that you are in too much of a hurry to launch for concerns such as proper service design won’t carry much water with users.

🖼️ Breakup summary screenshot via Ars Technica, Swiss cheese model diagram via Wikipedia

-

Or at least, they don’t have any excuse any more not to be mature. ↩