Governing AI

The UK Prime Minister, Keir Starmer, has announced some sweeping new AI policies which he hopes will “deliver a decade of national renewal”. The fact that the Politico piece flagging this announcement is entitled “Starmer banks on AI as his big economic plan falters” probably tells us most of what we need to know, but it’s worth diving in a little deeper to understand what is actually going on.

I already commented on the policy for a piece in BusinessCloud:

Dominic Wellington, enterprise architect at California tech firm SnapLogic, warned that “rushing untested initiatives to market is a risky endeavour, and the role of government should be to act as an impartial referee, not to join the fray”.

He offers as an example: “Recently, BBC data was repeatedly mis-summarised by Apple’s AI features, presenting people with distorted versions of news stories. The government can and should enforce safety in outcomes, and offer support to industry in achieving those goals.

“It can do this by mandating implementations of ‘guardrails’ in AI systems, and requiring their certification before they are deployed in particularly sensitive domains.

“Speed should not be the government’s own goal; instead it should focus on creating the conditions for private enterprise to operate at speed, and to do so without impacting the safety of users and citizens.”

This is a somewhat diluted and (necessarily) shortened version of my actual views. In my original draft I did look for something positive to say about the policy:

For instance, commissioning a new supercomputer is a laudable initiative, but given the speed at which technology evolves, the likelihood that its workloads in 2030 (or whenever it actually goes live) will have much resemblance to what we are trying to run today is very doubtful. On the other hand, there is an undoubted need for a centralised AI Energy Council that can show the benefits of central planning, aligning new data centre construction to power grid layouts, easy availability of water, and so on — as opposed to the deregulated US environment. Joined-up planning can have real benefits here, ensuring that new infrastructure construction projects are aligned with projected demand and do not place undue strain on shared resources.

The rest of my thoughts were, uh, less positive. Tom Morris has done the hard work of reaching for a past example of the UK government trying to jump on a technology bandwagon, and I won’t spoil his piece but simply recommend that you read the whole thing.

For my part, I would just like to refer back to the final lines of my draft comments (also unpublished):

Involving users more in the design and acceptance of AI-enabled services is likely to have a far better success rate in terms of actual adoption than forcing these features into use. As in private industry, there must always be a solid and quantifiable benefit on offer for the proposed addition of AI features, not just a nebulous fear of missing out or being left behind. Where that value is on offer, industrial actors and private citizens will seize it for themselves, without the need for artificial incentives. Government’s role then is to facilitate the conditions for them to do that, and to do so safely.

Yes, the VP of Nope rides again!

Reading the Room

There are various interpretations possible when governments make these sorts of pronouncements. Let’s go through them, on a scale of more charitable to much, much less charitable.

The Benefit of the Doubt

Government ministers, let alone Prime Ministers, are insanely busy people and cannot be expected to be deep into every issue. One moment they are being asked to deliver peace to the Middle East, then they have to pivot to education policy, and there’s always the economy looming. Now there’s this AI stuff that’s in the news, they’re being told that people like it and want it, and anyway it’s inevitable, they have to join in or they — and the country — will be left behind. So why not make some excited noises, offer some vague promises, and move on to the next thing burning up their inbox?

This means some advisors will have to come up with the meat of the policy, and with any luck they will roll in some more or less sensible things that they wanted to do anyway, try to make sure there is a certain amount of adult oversight, and hand over the prepared remarks for the PM to deliver.

Because That’s Where the Money Is

Okay, now a more cynical version of the above scenario: now the advisors who write the speech are not well-meaning civil servants and technology experts. Instead they are various flavours of grifters, from big government contractors trying to make sure they don’t miss out on their share of any money being spent, to the more noxious types who tried to get the government into NFTs and are still trying to make government-backed digital currencies a thing, in the face of a complete lack of desire or need for them. These people don’t care for AI, they just see it as the easiest lever to pull to direct torrents of public money into their own pockets.

Moving Further Upstream

But why start so far downstream? Your really sophisticated grifter softens up his marks well ahead of time. The buzz about AI being the future and anyone who isn’t all-in being left behind is not coming from nowhere, after all; people out there are creating and inflating that feeling of inevitability. That way, the argument becomes nicely circular:

1) AI is happening anyway; 2) If you don’t make AI happen here, it’ll happen somewhere else, because of point 1 above; 3) To make AI happen here, you need to spend scads of money Right Now!!1!

Left unexplained is why something inevitable needs quite so much investment to make it happen.

Follow The Money

The same questions arise when it comes to adding Generative AI (GenAI) features to voice assistants like Amazon’s Alexa. This is a product line that has never made a profit and has no obvious way to ever do so — but now, for some reason, Amazon is trying to wire Alexa up to a Large Language Model (LLM). The Alexa team is reportedly trying to address some significant problems, in particular “‘hallucinations’ or fabricated answers, its response speed or ‘latency,’ and reliability”, and working to “preserve the assistant’s original attributes, including its consistency and functionality, while imbuing it with new generative features such as creativity and free-flowing dialogue.”

The real question is how any of this investment is ever going to pay off. Right now, Alexa doesn’t have a revenue stream as such: people buy a device that runs Alexa, whether from Amazon or from a number of third-party manufacturers that embed the feature, and that is the last money that Amazon ever gets from them directly for the use of Alexa. The idea (I wouldn’t dignify it by calling it a theory) was that Amazon could break even or perhaps take a loss on the initial sale of the device because people would do their shopping by talking to Alexa and this would translate to increased sales for Amazon.

Obviously this did not happen. People use their smart assistants to set timers, to play music, and for very advanced users who have deployed multiple devices around their home, to summon their children to dinner without having to raise their voices. And that’s it. Nobody is shopping via Alexa, and nobody will tolerate their smart assistant suddenly blaring ads in their kitchen.

So… in that environment, where the business case is already deep underwater, where is the extra money going to come from to fund the very expensive LLM runtime? Nobody is sharing hard numbers, for obvious reasons, but it has been estimated that an AI-generated response might be costing Google ten times as much as a traditional response to a query.

That might still be okay (financially, at least, if still questionable on environmental grounds) if people were willing to pay ten times as much for those responses — but that does not appear to be the case. Microsoft was forced to back off from charging Office users $20 per month to use AI features that did significantly more than anything Alexa can be expected to deliver. Instead, Microsoft will shoehorn the charge into the general Microsoft 365 subscriptions, without giving users the choice to opt out.

Amazon doesn’t have that option with Alexa. People who have become used to accessing Alexa for free would balk at any subscription fee Amazon were to introduce.

It has been suggested that Amazon will avoid high charges for a future GenAI-enabled Alexa by using its own homegrown Nova models, announced at AWS re:Invent in December 2024, instead of paying for third-party LLMs. However, this home advantage also applies to Microsoft, as together with Amazon, they are the ones operating the backends of many of the AI models. If Microsoft couldn’t figure out a way to make Office users, who are already inured to intrusive “assistive” features, to pay for AI features that are at least somewhat useful, I really doubt that a chattier Alexa will be a winning financial proposition.

Where does this leave the UK government’s AI ambitions? Nowhere good, is the answer. Both Amazon’s AI-Alexa and Keir Starmer’s AI Opportunities Action Plan smack of FOMO and tech solutioneering, starting with the means in mind instead of working backwards from a concrete benefit, whether to customers or citizens.

AI Maths

Amazon is not sharing its business plans for Alexa, but the government’s own maths do not hold up. First we are told that “The IMF estimates that – if AI is fully embraced – […] these gains could be worth up to an average £47 billion […] over a decade.” But later in the same release, we hear of investments of £14B, £25B, £12B, and $2.5B. Yes, the last one is denominated in dollars, for no immediately obvious reason — but still, that list of investments already adds up to more than the promised benefits of £47B — over ten years, let us not forget. One wonders, of course, how many of those projected billions of pounds of nebulous benefits spring from the same sort of woolly thinking as the Alexa business plan of “sell them at a loss and make it up in volume”.

It’s a pity because many of the concrete proposals embedded in the government’s AI plan actually sound pretty sensible. Nobody knows that the National Data Library is, but planning the power grid around the demands that new data centres are likely to place on it seems sensible.

The problem is in the unrealistic promises that are being held out. The idea that this policy will “make the UK irresistible to AI firms looking to start, scale, or grow their business” is simply risible. It is not the lack of a hastily-cooked-up AI initiative that has lead to the gulf between startup outcomes in the UK as opposed to Silicon Valley, and the consequent lack of strong national champions.

I would have far preferred to see governments in the UK and elsewhere focus on mitigating or preventing some of the real harms that AI is already doing, instead of chasing a bandwagon — or being haplessly dragged along in its wake. The government press release was careful to list only positive applications of AI technology: helping the NHS diagnose patients faster, driving down admin work for teachers, or spotting potholes in roads. But the way most people encounter AI in their daily lives is in the shape of slop: a nonsensical image of Shrimp Jesus, a search engine result telling them to change their blinker fluid, or distorted breaking news stories that tell them the Hollywood sign is burning.

Unfortunately it seems that copyright is not the right tool here either. This sort of hard problem is where carefully thought-out leadership and, yes, regulation by government could make a difference. If a business case can be found, companies will not need any further incentives from the government to roll out AI, including in the UK. If that business case is not present, it is very unclear why the government should incentivise this field. This AI fever is not a case of using public money to jumpstart a technology with undeniable positive benefits like solar energy. Far from offering real benefits to both the economy and the environment, in fact, this is a technology with real and present harms, both in how it is created, and in how it is deployed and used.

None of this is to say that there is no value in AI and LLMs, or that these technologies should be banned or something equally drastic. I have personally worked on numerous projects where AI delivered real benefits — but the key to all of them was that they started with a problem that needed to be solved. The AI was the means to an end, not an end in itself — and in other cases where an LLM was not the right tool for the job, guess what? We didn’t use one!

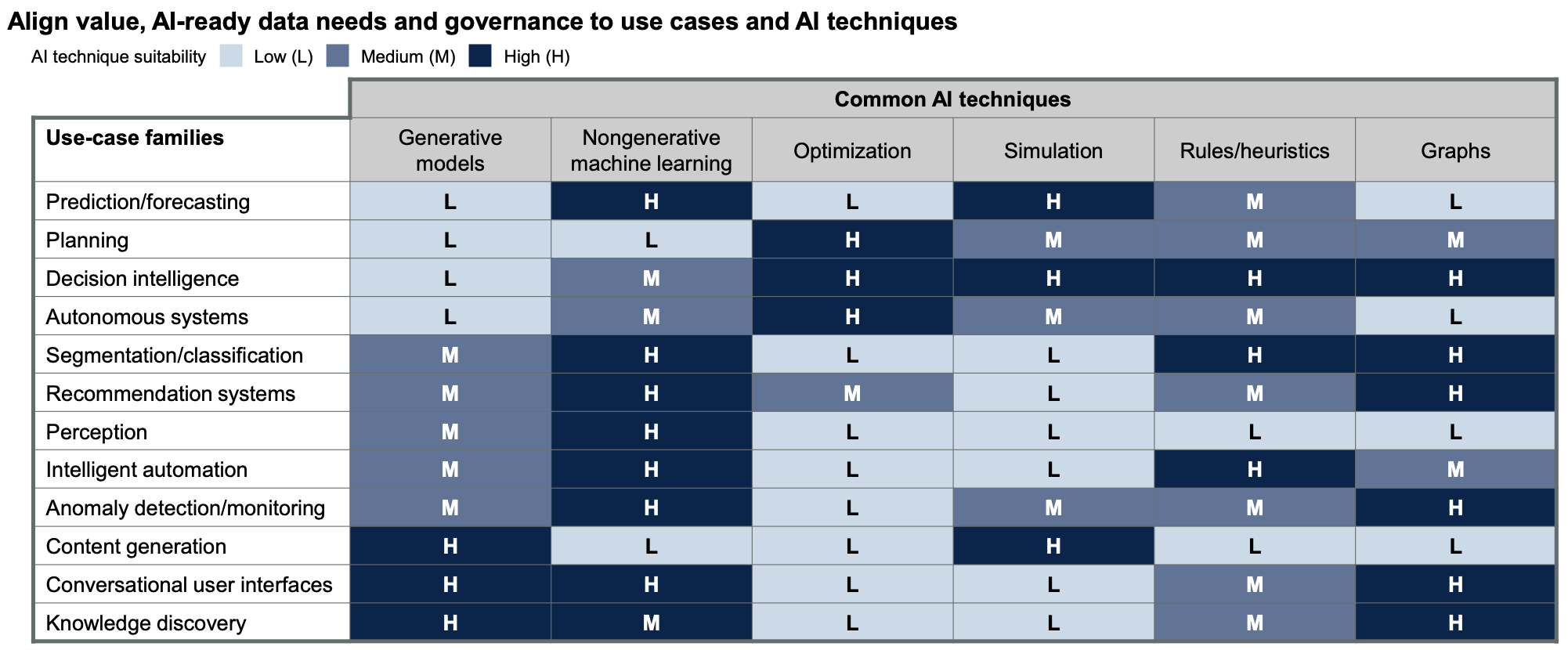

A recent Gartner webinar, “The Gartner 2025 Leadership Vision for Data & Analytics” with Rita Sallam, made the same point, mapping different use cases by their suitability to different AI techniques — and using a pretty broad definition of AI for the purpose, at that.

Bottom line, AI is “just” technology, and technology alone does not solve problems or trigger economic growth. Those good things happen when technology is applied in service to a goal. You can try to hothouse something for a little while, in government or in enterprise, but the odds of that forcing ever resulting in something viable that can live when the resources are withdrawn are vanishingly small. Better to use those resources on something that can make a concrete and lasting difference, whether for customers, users, or citizens.

🖼️ Keir Starmer photograph via Sky News; Gartner graph screenshot from webinar; Downing Street photo by Jordhan Madec on Unsplash