Closing the Books on AI

In January, as a sort of semi-official-but-still-deniable new year’s resolution, I started off trying to capture reviews of books I read in Apple’s Journal app. The problem is that only having access to the Journal app on the phone with its tiny on-screen keyboard turned the whole process into a huge drag, making my reviews increasingly terse and eventually tailing off entirely. I had assumed that Apple would get around to porting the Journal app to iPad in the fullness of time, as eventually happened with the Apple Music Classical app. However, WWDC has come and gone with no mention of Journal on iPad, so here we are.

One of the most anticipated announcements of WWDC ‘24 was Apple being dragged along kicking and screaming in the undertow of the still-building wave of AI hype. Apple Intelligence is probably the most cautious and least obnoxious way of adding AI to Apple’s platforms, but it is still getting criticised from both sides of the debate, for being simultaneously far too much and not nearly enough. Time will tell what the actual results will be; Apple Intelligence isn’t even going to be available in September with the first public releases of the various Apple operating systems, but is “coming later”, which most people assume to mean some time in the spring of 2025.

By a complete coincidence I found myself reading two (fiction) books back to back that incorporated the theme of AI in general and even LLMs in particular. I had preordered both of these months ago when they were first announced, so reading them so close together was just a coincidence of publishing schedules.

Service Model, by Adrian Tchaikovsky, has a robot as a viewpoint character — so far, so AI. There is a little exploration of what it means to be a robot in dialogue with human characters, but more by simply narrating the robot’s own cognition. Much like Martha Wells’ Murderbot, Tchaikovsky’s protagonist Uncharles has a radically non-human set of drives and priorities, mainly centred on ticking off tasks from a list. He is repeatedly accused of having contracted the Protagonist Virus — an accusation he vehemently rejects.

Apart from the obvious AI angle of all the robot characters, there is another aspect of the plot that is relevant to our current LLM-crazed time, but which requires a big

SPOILER WARNING

Seriously, if you haven’t read the book, you want to skip this next section, as it will unavoidably spoil the twist in the ending. I did guess at the rough outlines of it by about halfway through, but the details were still a surprise, and very well-executed.

Still with me? Okay, here we go.

The robot uprising that kills most of the humans is not a Terminator-style terror of AI run amok, nor even an uprising of enslaved machines. Horrifyingly, it is simply the end result of economic forces that we already see operating today. Quite simply, the robots took all the jobs, but there was no concomitant economic revolution. All the people made redundant (in both senses of the word) by robot labour were simply discarded by society.

We already see the same mechanisms with LLMs, even though they are far less competent than Tchaikovsky’s robots. As Cory Doctorow says, the AI can’t do your job, but the AI salesman can convince your boss to fire you and replace you with an AI anyway.

I am far from the first to point out that the concerns people have when it comes to AI are fundamentally concerns about capitalism. If you didn’t need to sell your art to live, why would you care that someone was making weird knock-offs of your art with too many fingers or weird teeth? But under capitalism, the plagiarism engines are actively depriving people of their livelihoods.1 In Service Model, Adrian Tchaikovsky simply takes these fears to their deadly ultimate conclusion.

A stylistic aside: I found the whole thing somehow reminiscent of Adam Roberts, in construction, style, and pacing. I would not have been surprised if the Farm had turned out to be Reading after all. And the Protagonist Virus is absolutely a Roberts-ian construction.

Done with spoilers

The other book I read was Moonbound, by Robin Sloan. In fact I was in the Bay Area on the day of the launch event for this book, but I was too jet-lagged to trek up from Peninsula, and badly needed some catch-up time with colleagues, so I missed it. This is a very San Francisco book (even if it does turn out to be set elsewhere), as much as Service Model is a British book. Both are post-apocalyptic, but where Service Model takes place in the dingy and dismal tail end of a collapse that is not yet quite complete, Moonbound takes place so long after the collapse that more than one civilisation has risen and fallen in the time since. This is a much more hopeful take on apocalypse: that however bad things may be, there is a bright future on the other side. Not only that, but the denizens of the successor civilisations have (incredibly, implausibly) learned from their predecessors’ mistakes. Some suspension of disbelief might be required here, more so than for the continent-spanning climate-management firm of the beavers or any of Robin Sloan’s other inventions.

Here, the narrator is again an AI, but this time one that is symbiotic with a human protagonist, who is set up to be the very embodiment of Tchaikovsky’s Protagonist Virus. The link with our LLMs of today is much more literal than in Service Model: the (unnamed) viewpoint AI claims direct descent from the language models, but even more so, the propensity of LLMs to follow story becomes a central aspect of the plot. This is an aspect that very much follows on from today’s generative AI, which is attempting first and above all to construct a plausible narrative.

Given Sloan’s textual fascination with AIs and San Francisco, a casual reader might be forgiven for expecting paeans to Andreessen-style techno-optimism. Having read his previous books, I was fairly sure that was not where he was going — and sure enough, the economic models that are described positively are cooperative and focused on externalities, not the curdling self-regard of our VCs of today.

The problem with books and AI

The coincidence of these two books coming to me so close to each other, together with AI being unsurprisingly a major topic of all my work conversations right now, let me see these parallels clearly. During that same visit to the Bay Area, we conducted a fascinating exercise: an “AI Red Team” — kind of a team-based version of my beloved VP of Nope.

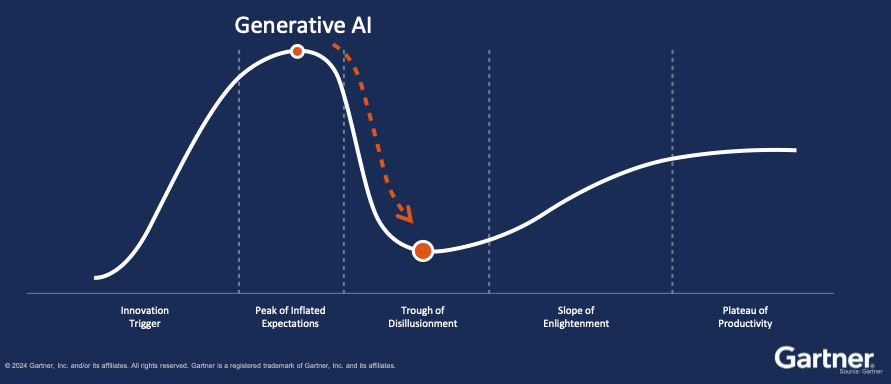

We were exploring the question of what happens if (when) the current wave of AI hype hits its inevitable downslope into the Trough of Disillusionment. Some argue that we are already there, but it’s always hard to call the tipping point except retroactively, and I still see a lot of momentum building. There were all sorts of technical concerns, but there was also a fascinating discussion around the brand of AI itself becoming toxic, to the point that technical capabilities are irrelevant in the face of public distaste for anything associated with AI.

Here is the third and final book-related coincidence of the week. As mentioned above, the concern with AI today is not that it will take people’s jobs by becoming better than a human at doing those jobs. The fear is that AI will be less capable but will take those jobs anyway on the strength of promised efficiency and consequent savings, which may or may not ever materialise — but in the meantime the people formerly doing those jobs need to eat. This is the Tchaikovsky robot apocalypse instantiated today.

One example of this process is how book recommendations are now swamped with AI-generated pink slime. Human writers, who were already struggling financially for a number of reasons, now see the results of their efforts sink without a trace in a sea of AI slop.

Where do we go from here?

We are at a crossroads — not a simple Y with only two branches to choose from, more like the Magic Roundabout which used to terrorise motorists in Swindon. This is not Apple’s intersection of Technology and Liberal Arts, more a violent collision of technological progress, VC-doped business models, and human and social consequences.

One possibility is that LLM and GenAI progress simply stalls out. There may be further asymptotic improvements, but they are so costly in terms of energy and compute that no business case will justify them. The concern then is what this bubble will leave behind. The Dot-Bomb left us with miles of dark fibre2 that powered the actual, real Internet revolution. The housing crisis did result in actual housing getting built. But what will be left if the current bubble pops? A whole bunch of Nvidia GPUs for gamers to descend on, but nothing much to fuel the next wave.

Another possibility is that public distaste for this technology rises to the point that it affects the addressable market. We already see the beginnings of this process, with users mocking Google relentlessly for shoehorning generative AI into its search engine so that it can (at vast expense) tell users to put glue on their pizza and eat rocks. End users are by and large not paying for the LLMs directly; AI is being added to services they already use, often for “free”, regardless of their desires. Vendors can therefore afford to ignore user distaste for a while, as long as they can sell to paying customers in the enterprise.

There are two problems with this approach. The first is that the current wave of AI investment is driven at least in part by extrapolations of massive consumer demand, based largely on the phenomenally rapid initial uptake of ChatGPT. However, it does seem that for most consumers, ChatGPT and its ilk are and remain novelties, not products they would pay for. AI vendors have therefore pivoted to enterprise customers, which to date have been dragged along by FOMO — but concrete applications of the technology are still few and far between. It remains to be seen whether the bubble can remain inflated long enough for that to happen, especially in light of the second question: what if AI is just not cool any more?

Consumer distaste for AI is already spurring legislation, and regulation has the potential to strangle application of this technology in many domains, rendering it in turn economically unviable even in domains that it would otherwise be well-suited for. By pushing too hard, AI boosters risk over-inflating and exploding the very bubble which sustains them, before valuable use cases and sensible regulation have time to emerge.

To quote one more writer, we need to ask the question “cui bono?” about every proposed application of AI technology. We are well past the time where “cool demo, bro” is reason enough to do something — and indeed, we are already seeing negative consequences from that approach. To protect the undoubted potential of the tech, we need to have serious conversations about where to use it, for what purpose, and to what benefit.

These are not just technology questions. As I keep having to remind people in my day job, it doesn’t matter if it works technically: the question is whether it does anyone any good. A reasonable prima facie way of measuring that is whether they are willing to pay for it. Until then, we have a market that is distorted by one of its important inputs being free at the point of consumption, with that distortion rippling out to all sorts of use cases that are only viable as long as that key input maintains a price point of zero or very close to it.

On the plus side, a realistic pricing of these services that takes into account their current cost and their current value can hardly avoid resulting in a resizing of the market. Once the tide of AI hype goes back out, we will see which use cases were swimming naked, to paraphrase Warren Buffett. This reappraisal will also put human workers and artists back on a more realistic footing for comparison, and perhaps avoid a Service Model-style financial robot apocalypse.

The downside of such a rebalancing is that anyone who bought into the hype too completely will end up high and dry. This is why every vendor adding AI features to their product should consider very carefully what could happen if (when) the bubble pops. Exploring useful AI features is good; coupling speculative components provided by third parties too tightly into fundamental architecture is giving hostages to fortune. Summon the VP of Nope, convene the AI Red Team, and examine your assumptions carefully.

🖼️ Book covers from author websites, AI Hype Cycle image from Gartner presentation, Magic Roundabout image from AeroEngland, photo of man by Razvan Chisu on Unsplash

-

I don’t buy into the accelerationist argument that if the situation gets bad enough, surely somebody will do something. There is no historical inevitability here: the way to stop the orphan-crushing is not to build the orphan-crushing machine in the first place. ↩

-

Not to mention all the lightly-used Aeron chairs. ↩